My recent journey through Uzbekistan ended on a powerful note. After a day spent exploring Nukus – the capital of the autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan in the country’s north – it was time to uncover more of what this remote region holds. Unfortunately, Karakalpakstan’s story is a rather sad one. In fact, the region is the backdrop of one of the most devastating human-caused environmental disasters in history.

The Aral Sea disaster

Back in the early 1960s, the Soviet Union started a massive push to turn Central Asia into a major export of cotton – or “white gold”, as they called it. They began rerouting water from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers – two major lifelines running through Central Asia – to irrigate vast cotton fields in some of the driest parts of the region. Uzbekistan ended up diverting a staggering amount of water, and by 1988, the country had become the world’s biggest exporter of cotton.

But this came at an enormous cost.

The Aral Sea, once the fourth-largest lake in the world, began to shrink rapidly. What was once a huge body of water gradually fractured into separate lakes, most of which dried up completely. By the 1970s, it had already lost the majority of its 67,000 square kilometres – and nearly 90% of its surface area is gone today, replaced by barren desert. The collapse of the lake destroyed local ecosystems. Fish species that had supported a thriving fishing industry disappeared. As the water receded, salt and toxic dust spread across the landscape, ruining crops and affecting the health of people living in the area. Furthermore, toxic chemicals from decades of pesticide and herbicide use seeped into the soil and water, worsening health conditions. At one point, the region had some of the highest infant and child mortality rates in the world.

Eventually, the dried-up seabed earned a new name: the Aralkum – Earth’s newest desert. Though there are efforts now to revive parts of the region by creating artificial lakes, the lakes of the former Aral Sea are still shrinking, and others have become so salty that they can no longer support wildlife.

Tour of the Aral Sea

That said, sometimes there’s an odd kind of beauty to be found in disaster. Karakalpakstan isn’t exactly on the typical tourist trail – especially compared to other parts of Uzbekistan – but it’s slowly gaining attention thanks to a rise in so-called “disaster tourism.” People are drawn to the region to witness the ship graveyards, walk the cracked seabed, and explore what’s left of the once-mighty Aral Sea. I was one of them. I’ve always had a fascination with abandoned places, so exploring this region was a must for me!

I joined a two-day tour organized by the Jipek Joli Hotel in Nukus, alongside three other travellers, each from a different part of the world. We covered around 900 kilometres – much of it off-road – and what we saw ranged from breathtaking to deeply sobering.

Mizdakhan Necropolis

Our first stops weren’t directly connected to the Aral Sea, but they were fascinating nonetheless – and a welcome way to start the journey. We left Nukus at 8 AM and headed towards the town of Khujayli, where two remarkable historical sites were waiting for us.

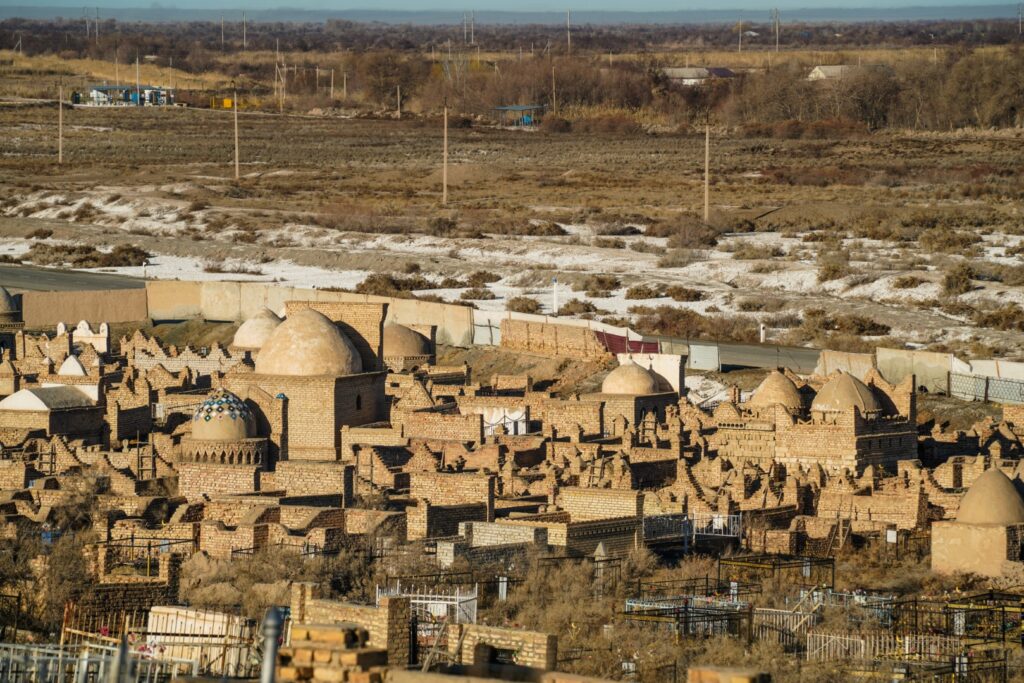

Our first stop was the Mizdakhan Necropolis. For this stop, we had a local guide named Ahmed, who shared a wealth of knowledge about the site. Mizdakhan was originally founded in the 4th century BC and remained inhabited for nearly 1,700 years. At its height, it was the second-largest city in the ancient Khorezm region, which now spans parts of modern-day Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

The city thrived for centuries, but its fate changed in the 14th century when Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur of the Timurid Empire launched three brutal campaigns against Khorezm. Mizdakhan was destroyed in the process and eventually abandoned as a settlement. From then on, it served solely as a burial ground. Most of the mausoleums and the small mosque that stand on the hill today date back to this period.

Gyaur-Kala, a Zoroastrian fortress

From Mizdakhan, we could see the ruins of Gyaur-Kala, a Zoroastrian fortress perched on a nearby hill. Thought to date back to the 4th century BC, it’s among the oldest structures in Uzbekistan. The fortress was once part of a chain of defensive outposts protecting the ancient borders of Khorezm. Its ten-metre-high walls, though partially collapsed, encircle the remains of two citadels.

According to local belief, Gyaur-Kala was once a major centre of Zoroastrianism. Some say it was here that the sacred Avesta texts were written by Zoroaster himself, and that followers of the faith would gather within its walls to hold ceremonies, trade goods, and take shelter during times of unrest.

Our guide had returned to Nukus by this point, so when we reached the site, our driver simply pointed towards the hill. The four of us climbed up on our own and wandered through what remained. There’s not much left now – just fragments of the fortress walls and bits of pottery scattered across the ground.

Dromedary camels, camel milk and a whole lot of cute goats

Once we made our way back down from Gyaur-Kala, we had a 2,5-hour drive ahead of us to reach the town of Moynaq, located at the former shore of the Aral Sea. Not long into the journey, we had to pause for a herd of dromedary camels lazily crossing the road – a surreal but very Karakalpakstan moment. As we continued deeper into the region, the signs of environmental collapse became more obvious. We passed fields laced with white salt crusts – a stark reminder of one of the many consequences of the disaster.

After a long stretch of incredibly bumpy road, we arrived in Kungrad, the last major town before Moynaq. We made a quick stop to stretch our legs, take a few photos, and use the toilet before hitting the road again. From there, the drive only got rougher. Our driver was constantly swerving to avoid deep potholes, his focus unwavering as he dodged bumps and oncoming cars with practiced ease.

Not long before reaching Moynaq, the driver suddenly veered off onto an unpaved road. We ended up in a small rural settlement – a cluster of modest homes surrounded by dry steppe. A few friendly locals came out to greet us and gave us a little tour of their village. We petted baby goats and dogs, saw camels and horses up close, and even got to try camel milk. It reminded me a lot of the fermented horse milk I had back in Kyrgyzstan – thick, salty, and intense. I only managed a single sip before politely handing it back. Definitely an acquired taste.

Moynaq and the ship graveyard

As we continued towards Moynaq, we passed through a few tiny villages that seemed to appear out of nowhere, scattered across the vast emptiness of the steppe. Surprisingly, they didn’t look abandoned at all – contrary to what I’d imagined, given the scale of the disaster. Life, somehow, carries on.

Once we reached Moynaq, it was lunch time. We stopped at a local guesthouse where we were welcomed with hot soup, fresh bread, tea, and a spread of snacks – simple but hearty, and much appreciated after the long, bumpy ride.

Then came the part I had most been looking forward to: the ship graveyard.

Once a bustling fishing hub and Uzbekistan’s only port city, Moynaq was home to tens of thousands of people. Today, the Aral Sea has retreated over 150 kilometres from the town, and its population has dwindled to just around 13,500.

Below the town’s old lighthouse, a haunting row of rusting ships sit stranded in the sand, lined up like gravestones. Behind them, a vast desert stretches out where waves used to roll in – miles of cracked earth, scattered seashells, and dry scrub.

We stopped by the small museum near the site, which houses a modest but moving exhibition: paintings, photographs, and a short film documenting the Aral Sea disaster and Moynaq’s former life. Then we headed down to the ships themselves.

We took our time walking among the metal skeletons, climbing aboard one of them to get a better view. I stood on the deck of its rusted hull and looked out over what used to be the sea. It was hard not to feel the weight of it all. The quiet out there isn’t peaceful – it’s heavy. I walked out a little way onto the dry seabed, thinking about the people who once made a living from these waters, until the sea vanished and left nothing but sand and dust.

Across the Aralkum Desert to the Ustyurt Plateau

From Moynaq, we took the only road heading west, across what was once the seabed of the Aral Sea. We passed a natural gas facility, one of the few sources of employment for those who stayed behind after the sea disappeared. Beyond that, the road all but dissolved into the desert. The ride became even rougher, with long stretches of bone-rattling bumps as we pushed deeper into this dry, desolate landscape.

We were headed for the Ustyurt Plateau, a vast transboundary clay desert shared by Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. Covering about 200,000 square kilometres, it sits at an average elevation of 150 meters and is framed almost entirely by dramatic escarpments known as chinks. These cliffs form otherworldly landscapes and are often streaked with layers of pale pink, blue, and white.

After 2,5 hours of driving across Earth’s newest desert, we slowly ascended the plateau. At the top, we pulled over to take in the staggering view. The Aral Sea’s former bed stretched endlessly before us, a vast expanse of sand and salt extending as far as the eye could see. The road we had just driven – snaking through the empty seafloor – looked unreal from above. In the distance, faint but still visible, was Moynaq, about 60 kilometres away.

We all agreed to fall silent for a few minutes. In that moment, surrounded by emptiness, the silence was almost sacred. It was magnificent – nothing but the sound of wind, and the weight of everything unspoken.

A little further down the road, we stopped at Aral Canyon, one of the most visually striking features of the plateau. Towering cliffs with unusual rock formations carved by the disappeared sea offered a view even more impressive than before. Moynaq remained a tiny dot on the horizon, and beyond that, there was nothing – just the endless desert that used to be sea.

We continued bouncing along the broken roads towards the southern edge of what remains of the Aral Sea, where we’d spend the night in a yurt. But just before sunset, golden light bathed a small, unexpected site in the middle of nowhere: the ruins of a 16th-century cemetery. The old Kazakh and Karakalpak tombs stood quietly among the dust, their stone markers engraved with ancient symbols.

Moonlight over the yurt camp

We watched the sun set over the Ustyurt Plateau from the back of the truck, the sky glowing with shades of orange and pink. Just as dusk settled in, we caught our first glimpse of the Aral Sea, shimmering faintly in the distance. Then, as if perfectly timed, a blood-red moon began to rise over the water. It was an absolutely breathtaking moment, one of those rare instances when nature seems to choreograph itself just for you.

The yurt camp we arrived at was much larger than I’d expected – around 20 to 25 yurts, plus a separate building with toilets, a shower room, and a shared kitchen and lounge. It wasn’t quite the remote, off-grid experience I had envisioned, but honestly, I didn’t mind at all. The camp was cozy and welcoming – and with a stunning view too, as it is perched on the edge of the Ustyurt Plateau, overlooking the Aral Sea. I shared a warm, beautifully furnished yurt with another female traveller, complete with actual beds – far more comfortable than I’d anticipated. Dinner was delicious – a hearty, home-cooked meal that hit the spot after such a long and eventful day.

Later that evening, I wandered off on my own for a short walk to take in the night sky. I climbed a small hill to escape the camp lights, hoping to catch a glimpse of the Milky Way. Unfortunately, the moon was so bright it washed out most of the stars, but I didn’t mind. I found a rock to sit on and soaked in the silence, the moonlight glinting off the water, stars twinkling faintly overhead. It was the perfect end to an unforgettable day, before heading back to the yurt and curling up for a really comfy night.

Sunrise over the Aral Sea

In the morning, one of the staff members kindly prepared a bucket of warm water for me to shower with. I had an overnight train to catch later that day and wasn’t keen on boarding it feeling grimy. Stepping into the shower room was a bit of a shock – the air was freezing – but the warm water made it more than worth it. By the time I was done, I felt like a whole new person.

When I stepped back outside, the sky had already begun to lighten, revealing a gorgeous pink hue stretching across the horizon above the Aral Sea. I grabbed my camera and set off for a quiet walk along the edge of the plateau. I followed the ridge to a small canyon, watching as the sun slowly rose and bathed the landscape in golden light. The views were absolutely breathtaking – easily some of my favourites from the entire trip.

Mys Aktumsyk Canyon

Back at the camp, breakfast was ready and waiting – a simple but satisfying start to the day. After eating, it was time to pack up and brace ourselves for more bumpy roads. We descended from the plateau and followed its base for a while. Then, without warning, our driver veered off-road and began climbing back up the plateau. At the top, he stopped at the edge of a stunning canyon known as Mys Aktumsyk. The view was jaw-dropping – layers of pink, blue and white rock carved by time, stretching out in every direction.

While the driver headed back down with the truck, the rest of us lingered above, taking photos and soaking in the landscape. It felt amazing to finally stretch our legs and walk after so many hours of being jostled around in the truck. We slowly made our way down the slope to meet the truck again, enjoying every step and the incredible views all around us.

Touching the Aral Sea

We followed the shoreline of the Aral Sea for a while, passing several camps where locals collect brine shrimp. Our driver mentioned that they can earn up to 2,000 USD for just 50 kilograms – which definitely put into perspective the quiet bustle we were seeing in such a remote, seemingly desolate place.

Not long after, our driver veered off down a rough, makeshift dirt track leading towards the sea. He pulled over a few hundred metres from the shore and told us we’d have to walk the rest of the way – if the truck went any farther, it would likely sink into the soft ground.

I took off my shoes and socks and stepped into the cool, squelching mud, which gave way to thick, crusted salt flats near the water’s edge. It felt oddly satisfying to walk barefoot through the sludge. As I stepped into the sea, each foot sank slightly with the weight of my movement. I didn’t venture far – something told me it wasn’t wise – but just feeling the salty water around my feet was surreal.

The view from the shore was one of my favourites of the entire trip. The sea was eerily still, almost lifeless, and the sunlight reflected perfectly off its glassy surface. The silence, the stillness – it felt like standing on the edge of another world.

Kurgancha-Kala fortress

Even though I insisted I didn’t need to wash my feet, our driver wouldn’t hear of it. He turned the truck back towards the yurt camp, where yet another bucket of warm water had already been prepared for me. I was honestly blown away by the kindness and thoughtfulness of the Karakalpak people!

Soon, we were back on the road, though it wasn’t long before our next stop: the ruins of Kurgancha-Kala, a 12th-century fortress. It once served as a frontier outpost on the northern edge of the Khorezm region, and possibly even as the last caravanserai for Silk Road merchants brave enough to cross the barren Ustyurt Plateau.

Standing there, in what today feels like the absolute middle of nowhere – no paved roads for hundreds of miles, no signal, just wind and silence – it was surreal to imagine that centuries ago, this place was bustling with the sounds of traders, animals, and stories being shared from across continents. A vital waypoint on one of history’s most iconic trade routes, now reduced to decrepit walls.

As we approached the checkpoint for entering and exiting the Aral Sea area, we stopped briefly to pet a friendly dog and take one last look at the sea behind us. Then we drove on, deeper into the vast, seemingly endless desert. At one point, we spotted a small member of the Mustelidae family – maybe a weasel or stoat – darting across the road. It paused just long enough for us to catch a glimpse before disappearing down a hole, safely out of sight.

The village of Kubla-Ustyurt

We made a stop in the small village of Kubla-Ustyurt, built in 1964 along the route of a gas pipeline. Around 500 people live there today. Our driver explained that most of them work at the nearby GazProm compressor station, and that there’s good money to be made there. According to him, life in the village is peaceful and comfortable – and honestly, it felt that way to me too.

While the houses might be considered modest or even run-down by Western standards, there was a sense of calm and contentment that was hard to miss. People greeted us with smiles and waves as we passed through. I could easily see the appeal of living in a quiet, remote place like this. Life here seems safer, simpler – and probably more connected. I imagine a strong sense of community, where people genuinely look out for one another.

We bought some warm, freshly baked naan bread straight from a roadside oven – simple, perfect travel food – and continued our journey across the desert. As we left the village, we drove over its old airstrip, which is no longer in official use, except for emergencies. Out in the distance, we saw three camels slowly crossing the desert. Dust devils danced on the horizon, twisting up from the cracked earth like little desert tornadoes.

Urga, an abandoned fishing village

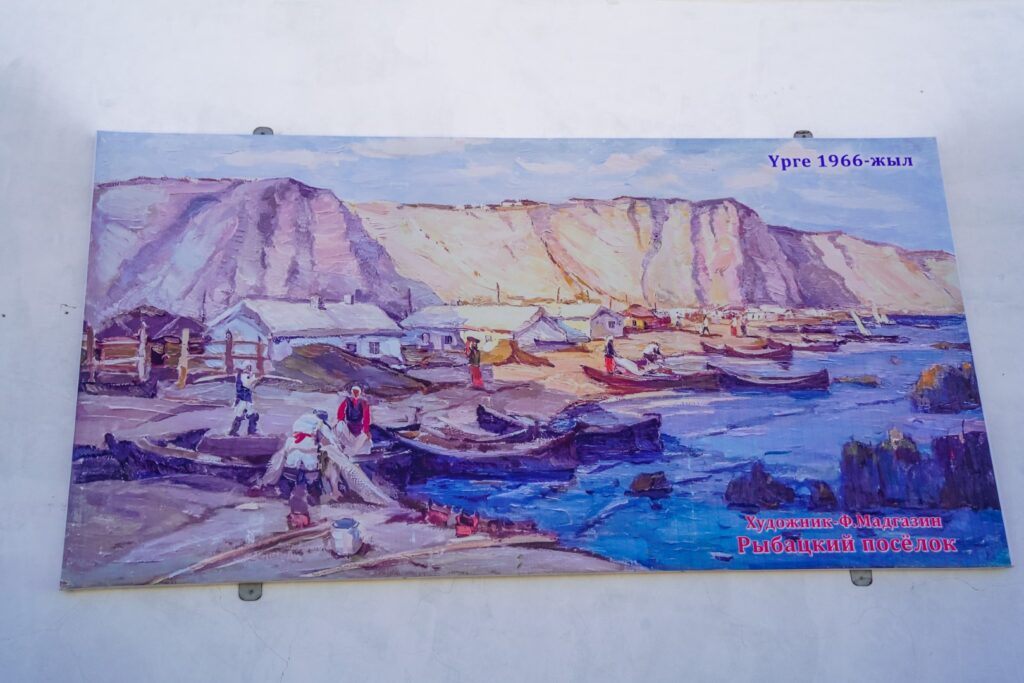

Our next stop was the abandoned fishing village of Urga – and hands down, this was my favourite cultural stop of the whole tour. Something about it resonated deeply with me, especially because I couldn’t help but see parallels to the abandoned villages in the Faroe Islands that I’ve researched.

Urga sits on the edge of Lake Sudochi, which used to be a major reservoir in the Amu Darya delta. It was once connected to the Aral Sea via a narrow channel, but as the sea began to shrink, the connection was severed. The lake fragmented into smaller pools, and the area’s rich ecosystem collapsed along with it. What had been a vibrant fishing port turned into a ghost village. Urga was actually one of the first Russian settlements in the Khorezm region, founded by fugitives. It remained inhabited until 1971, when the few remaining fishermen were finally forced to leave.

Our driver parked near the old cemetery that sits just above the village, and we walked down from there, the path offering stunning views over the lake. Once we reached the village, I stepped into the old, crumbling fish factory. The structure was eerily familiar – it reminded me so much of a ruin I’d visited back on the Russian forest steppe in 2019!

I wandered down to the lake’s edge and noticed a few rotten wooden posts poking out of the mud – maybe the remains of a dock, or possibly a foundation of some long-lost house. When I made my way back to the village ruins, I spotted a low, half-buried building. Inside were two rooms, still mostly intact. One of them had a rough stone fireplace in the centre. Later, the driver told me that this building had once been used a a refrigerator.

Shortly after leaving Urga, we stopped at another ruin perched on an elevated point with a sweeping view over the lake. From up there, our driver pointed out a river snaking off into the distance – into Turkmenistan. He explained that water from this river is now being diverted, further draining Lake Sudochi. Even after everything the region has already endured, the environmental disaster continues.

This was our last stop before heading back to Nukus – a long drive through stretches of desert and scattered villages. We paused for a late lunch at a roadside café in the village of Ktai, just outside Kungrad. We were free to choose from the menu, so I went for a veggie pasta and a Sprite. About an hour and a half later, we were back in the city – just under two hours before my overnight train to Beyneu in Kazakhstan. At the hotel where our journey had begun, the staff surprised us with traditional Uzbek hats as parting gifts – red for the women, black for the men. A perfect keepsake to remember an unforgettable trip.

As the train pulled out of Nukus, I found myself reflecting on the strange, stirring beauty of the last two days. Karakalpakstan had given me more than I expected – more desolation, more silence, more depth. It’s a place shaped by catastrophe, but it hasn’t lost its soul. Between the rusting ships, abandoned villages, endless desert, and warm hospitality, I felt both the weight of history and the resilience of life. It’s not an easy travel destination, but it is a necessary one.

Leave a Comment