The border between Denmark and Germany is a complex matter. It has changed many times during the course of history and it wasn’t until 1920 that it became what it is today. And although it was rarely settled in a peaceful manner, today, the border region is a brilliant example of friendship and cooperation between two countries.

A border separating Denmark with the rest of continental Europe was first established in 811 AD in the treaty of Heiligen. The swampy Eider formed the natural land border between Denmark and the Frankish Empire. But several centuries beforehand, the fortification system known today as the Danevirke had been initiated in what is today Germany’s part of the Cimbrian peninsula.

Before the Second Schleswig War in 1864, the now-German historical duchy of Schleswig was a fiefdom of Denmark with the border still running along the Eider. However, in 1864, Prussia conquered Schleswig and the new border moved approximately 150 kilometres north to Kongeåen where it remained until 1920 when the current 68-kilometre-long border was established about 50 kilometres to the south, as determined by the Schleswig referendum. The new border followed a loosely defined language border.

But like any unnatural border, the present-day border comes with consequences. Approximately 50,000 ethnic Danes belong to the Danish minority in Schleswig-Holstein, and on the other side of the border, approximately 15,000 ethnic Germans reside in Sønderjylland. However, as mentioned above, the amicable cross-border cooperations serve as an example to the rest of the world. While Denmark and Germany don’t share the same official language, both languages are present on either side of the border. North of the border, students are taught German in public schools, and south of the border, Danish is an optional subject. The border region exists as a shared living space with freedom of movement and a cross-border bond rarely found elsewhere.

However, in 2020-21, the Covid-19 lockdowns put a temporary stop to the free travel between Denmark and Germany. Denmark closed its borders and Germany followed soon after. Stuck in the middle were those that live in the border region. But for one family, the border placement has always been an odd situation.

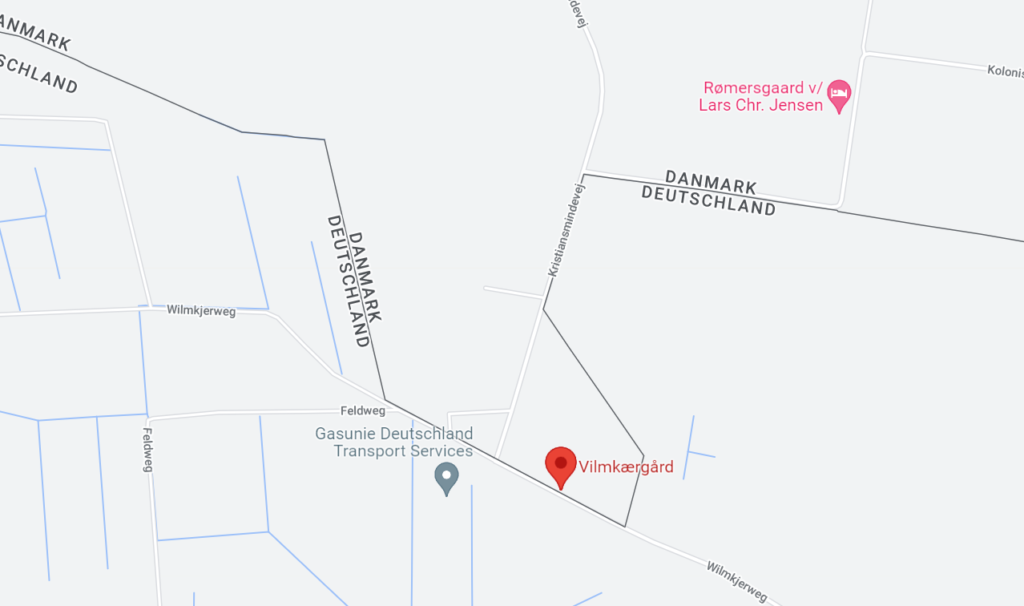

North of the German town of Ellund, in a little pocket of Denmark, lies their farm, Vilmkjærgård. Back in 1920 when the current border placement was being decided, the family asked to remain in Denmark, so a compromise was made and the border was pulled down to the edge of the courtyard. The German road, “Wilmkjerweg”, which is named after the farm, is the only way to the farm. On the Danish side of the road lies the farmhouse and most of the courtyard, on the German side stands the old barn. Every time the family wants to go anywhere else in Denmark, they have to take a little trip to Germany first.

After the new border was established, a new Danish road, Kristiansmindevej, was built, connecting to Wilmkjerweg, and the farm residents and guests were given treaty rights to enter Germany without passports to reach the farm. However, this didn’t come without problems, as the Danes were arrested and held by German police several times until the misunderstanding had been cleared up. It was especially a problem during World War II, as the residents were harassed by the Germans who often arrested them for entering Germany “illegally”. Until Denmark joined the Schengen Area in 1996, crossing the border at Vilmkjærgård was only allowed with special permissions, but since it’s the only border crossing that never had a barrier, one could easily just cross over to the other country.

As a chaser of the unusual and odd borders of the world, I just had to visit this farm on my way south to Büsum where I was going to catch a ferry to Helgoland the following day. I left the highway towards Flensburg shortly before the border and crossed it via Kristiansmindevej. I didn’t see any border control whatsoever, not even a sign or anything indicating that I was leaving one country and entering another. I entered Germany and parked on the side of the road before walking to the farm to admire this geographical oddity at the edge of Denmark.

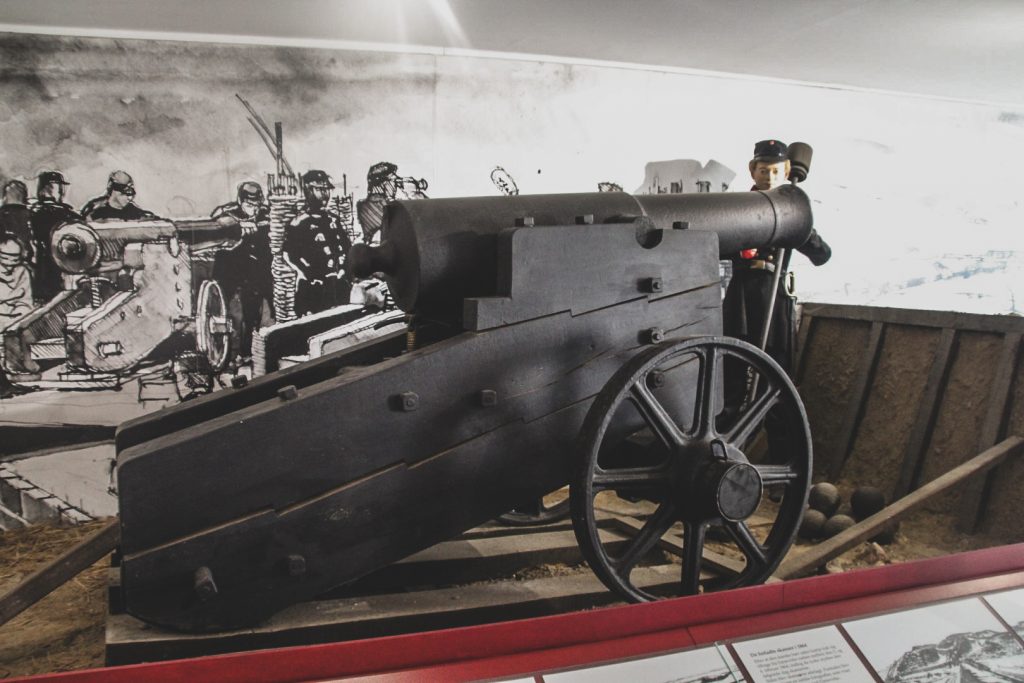

Driving further south into the old “Danish” part of Germany, I headed to the Danevirke Museum to see the large fortification system with my own eyes. Despite its geographic location in Germany, Danevirke (which literally means ‘earthwork of the Danes’) is considered the largest prehistoric monument of Denmark, and I believe it’s something all Danes should see at least once in their lifetimes. It played a crucial part in our history as a nation.

The Danevirke consists of 30 kilometres of ramparts, stretching across the Cimbrian peninsula from the former Viking trade centre of Hedeby on the Baltic coast to the marshlands in the west. According to a legend, it was Thyra Danebod (935-958 AD), wife of King Gorm the Old and mother of King Harald Bluetooth, who was responsible for the building of Danevirke. However, archaeological findings date the first building process to the Nordic Iron Age, before 500 AD. With the help of dendrochronological dating, it has been established that the main structure was built in three phases between 737 and 968 AD, seemingly to protect against an invasion by the Frankish Empire. The Danevirke was expanded several times since, and it was even used for military purposes as late as 1864 – the decisive war when Denmark lost Schleswig to Germany. The Danevirke was a powerful symbol for Denmark then, and it remains so today, despite its geographic location.

The small museum gave me a great introduction to the place, before venturing out to see it for myself. Parts of the Danevirke were being renovated, but I managed to find a section of the grassy rampart that lead me through a beautiful forest and past green meadows to Thyraborg, the remnants of a fortress believed to have been built under Valdemar the Great (1154-1182 AD). This area is the most visited part of Danevirke, but the remains of it stretch for 30 kilometres so there is plenty more to see. If I’d had time, I would’ve loved a hike along the entire rampart.

Luckily, I did have time to visit one more place that day. I drove to Hedeby (or Haithabu in German), which was the first larger town in Denmark, founded in the Viking Age (8th-11th century AD) as a centre for trade. The town was located at the head of the narrow inlet known as the Schlei, which connects to the Baltic Sea. A strategically important location on the major trade routes between the Frankish Empire and Scandinavia, and between the Baltic and the North Sea, prompting Hedeby’s success. Along with the towns of Schleswig and Birka in Sweden, Hedeby’s status as a major international trading centre served as a foundation of the Hanseatic League, a major commercial and defensive confederation between the late 12th century and the 15th century.

Despite its trading success, life in Hedeby was anything but easy. The town was made up of tiny townhouses, built closely together. Tuberculosis and other diseases thrived in the crowded town, and people rarely made it past 40 years of age. Around 965 AD, Spanish traveller and chronicler Ibrahim ibn Yaqub described Hedeby as “a very large town at the extreme end of the world ocean… The town is poor in goods and riches. People eat mainly fish which exist in abundance. Babies are thrown into the sea for reasons of economy.”

During a conflict with King Svend Estridsen of Denmark, Norwegian King Harald Hårderåde set Hedeby on fire by sending burning ships into the harbour. The town was further destroyed in 1066 by the West Slavs, after which it was abandoned. Instead, the town of Schleswig was founded on the other side of the Schlei. In the following centuries, the remains of Hedeby disappeared completely due to rising waters, and the location of the abandoned town was eventually forgotten.

Hedeby was rediscovered in the late 19th century and excavations began shortly after. The site was very well preserved due to being waterlogged and never built on since its destruction. Despite almost 100 years of intermittent excavations, only a small section of the old town has been investigated, so there is still much that is unknown about life in Hedeby.

In 2005, a reconstruction of the town was initiated at the original site. Based on the archaeological findings, some of the original houses were rebuilt. This was what I wanted to see.

I parked my car somewhere in the countyside, near a section of the Danevirke, and followed it for quite a while down to the sea where the open air museum lies. I got there at 5.52 pm and they were about to close, but the ticket guy said I was welcome to walk around for free until closing. That was so very nice of him! Although it was a short time, it was wonderful to get to see the reconstructed houses in their original location. I know that life in Hedeby was tough, but I couldn’t help but wonder if they appreciated just how cozy it was, too.

My day of borderland sightseeing had come to an end, but I had one more place I needed to go before making my way to the ferry to Helgoland. I had forgotten a few items in Albersdorf when I went there for a Stone Age gathering in July, and since it’s near Büsum, I picked them up on the way. I ended up staying for the night in my car as four of my friends were there. It was so nice to spend an evening by the campfire in the most beautiful and authentic Stone Age environment I’ve ever seen. A lovely way to end the day!

Leave a Comment